Clew: Behind the Name

I learned how to knit during my first year of college, sandwiched between my two “big sisters” on an saggy couch that had seen better days. Angie was a neo-rockabilly babe from Atlanta, and Amy an applied mathematics major who loved nothing more than to watch Xena: Warrior Princess and let her needles fly. My first completed project was an abomination of a scarf in traffic cone orange. I never imagined that twenty-five years later, I’d be an amateur fiber artist and perpetually surrounded by balls of yarn.

For even longer than I've been winding balls of yarn, I've immersed myself in mysteries, following threads of clues alongside detectives from amateur sleuth to hardened Chief Inspectors. My journey began with Nancy Drew (for obvious reasons) and Encyclopedia Brown, then graduated to Agatha Christie around age ten. I devoured the foundations of the genre: Edgar Alan Poe, Wilkie Collins, and Arthur Conan Doyle. The Golden Age of Detective Fiction became my literary home, particularly the grand dames: Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, Margery Allingham, Patricia Wentworth. In my early twenties, I worked my way through Rex Stout's Nero Wolfe series, borrowing well-worn volumes from the personal library of a family who paid me to babysit. Later came a noir phase — Hammett, Chandler, and the MacDonalds — though I eventually got tired of their battered women and casual violence. Throughout it all, I've loved words: their histories, their hidden meanings, their power to reveal and conceal.

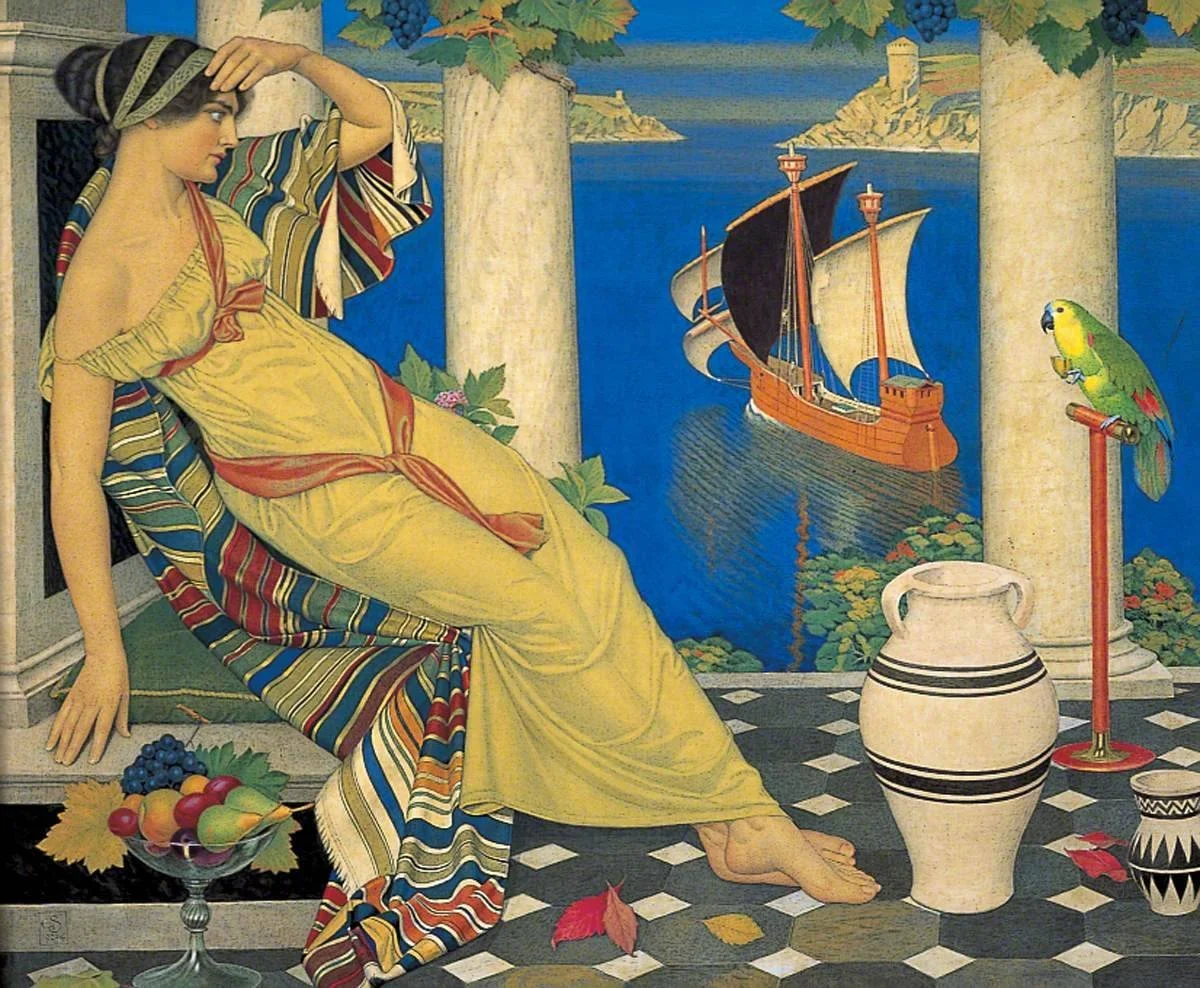

When a Merriam-Webster Word of the Day entry revealed that the modern word "clue" originated from "clew" I was thrilled to discover a connection between two disparate passions. The etymology traces back to Greek Mythology. Clever Ariadne fell in love with Theseus at first sight. So, the night before he entered the labyrinth to slay the Minotaur, she gave him a clew — a ball of yarn. She told him to unravel the yarn as he wound his way through the maze so that he could find his way back out again. Thus, this humble gift both saved his life and secured his place in legend. (Unfortunately for Ariadne, Theseus soon abandoned her on the small island of Naxos. She woke from sleep to find her husband’s ship sailing off into the horizon so that he could marry her younger sister.) For years, the origin of the word clue was the kind of trivial ephemera that secretly delighted me. In 2020, when I was setting up an LLC, I didn’t have to think very long to find a d/b/a for my consulting work.

Southall, Joseph Edward. Ariadne on Naxos. 1925, Birmingham Museums Trust, Birmingham.

In a detective story, the frustrated witness doesn’t understand why they’re being asked to repeat their account over and over. “I’ve already told my story five times,” they’ll whine. But even a flat-footed beat cop knows that stories are dynamic, living things. Each new telling has the potential to bring to light a forgotten detail, or unravel a web of lies.

Recently, I listened to Mark Haddon's short story "The Mother's Tale," in the collection Dogs and Monsters. Although set in Renaissance England, it’s obvious that this work is a retelling of the Minotaur myth. The "monster" is merely a child, seemingly born with a physical difference. The salacious story of the bull is created to shame the mother and protect the king's vanity. Told from the point of view of the mother, the woman we know as Phaedra observes:

“The truth is dull fare and we are dangerously enamoured of the extraordinary. These days if I read or hear some glittering tale, and find my attention being held fast, I ask myself, what suffering might these fabulous events conceal? Where am I being encouraged not to look? Who benefits if I am distracted and do not witness the mundane round of ordinary cruelty?”

Source: Haddon, Mark. Dogs and Monsters: Stories. United States, Doubleday Canada, 2024

I always considered the myth that gave us the word clew from Ariadne’s point of view as a cautionary tale. What woman cannot relate to this story? She lends her brilliance to a male counterpart, assuming that he’ll be so grateful that he’ll bring her along as he conquers the world; he abandons her as soon as it is convenient. History is littered with stories of women's work as the stepping stones for mens’ advancement, while their own stories are reduced to footnotes, if not erased entirely.

But “The Mother’s Tale” pushed me to look deeper, beyond my own identification with Ariadne's plight. What other voices had been silenced in this telling? What suffering lay beneath the polished surface of this heroic tale? In Haddon’s story, the mother's perspective reveals new dimensions of grief, love, and moral complexity that traditional telling strategically obscures.

It's a reminder that the most vital clues often lead us not to simple solutions, but to more profound questions. In my work, I seek to follow threads of inquiry wherever they lead — even when they guide us away from comfortable narratives and into challenging territory.

Does my business even need a brand name? After all, I’m most often hired on the strength of my personal reputation. But I chose a name that could grow with me. Already, “Clew” has grown beyond a private connection between my love of mysteries, fiber arts, and etymology. It's a reminder that the most vital clues often lead us not to simple solutions, but to more profound questions. In my work, I seek to follow threads of inquiry wherever they lead - even when they guide us away from comfortable narratives and into challenging territory. Like the detective who knows to keep asking questions, I've learned that truth rarely lies in the popular, beloved version of any story.

That's the real genius of Ariadne's gift. The thread that guided Theseus through the labyrinth wasn't an escape route; it’s an invitation to examine who gets to be the hero, who gets labeled as a monster, and whose comfort we preserve by upholding the status quo.